Gunter at Howe 2017

This is game number 745 in Howe Bulldogs history and Howe has an overall record of 381-339-24 since the initial UIL game in 1935.

THE BULLDOGS ENORMOUS SUCCESS

The Bulldogs are 24-8 in their last 32 games. The teams that have beaten Howe in those last eight losses had a combined record of 95-15 and three state championships and 30 playoff games.

2014: 27-21 loss to Leonard (9-2, lost to eventual state champ Waskom in the second round).

2014: 71-21 loss to Waskom (15-1, eventual state champions).

2015: 49-7 loss at Pottsboro (11-1, two-round playoff team).

2015: 31-14 loss to New London West Rusk (12-2, lost to eventual state champ Waskom in the third round).

2016: 42-14 loss at Gunter (16-0, eventual state champion).

2016: 35-7 loss to Pottsboro (11-3, lost in the fourth round to eventual state champion Mineola).

2016: 39-36 loss at Van Alstyne (7-4 record, lost in the first round of the playoffs to Sunnyvale).

2016: 21-7 loss to Mineola (14-2, eventual state champion).

HOWE’S INCREDIBLE RECORD-SETTING OFFENSE

In 2016, Howe averaged 385.31 total yards per game, which is the most in school history. The Dogs rushed for 4,473 of the total 5,009 yards which was also most in school history. They broke the previous high record of 4,535 (377.92 yards per game) which was set in 2015.

Howe’s offense ranked fourth all-time in school history with 30.92 points per game. The most ever is 34.17 set in 2015.

Since 2013, Howe has averaged over 28.69 points per game. That has never before happened in a three-year period in Howe’s 73 seasons.

Since 2013, Howe has 26 wins. That also has never happened in a three-year period in Howe’s 73 seasons.

HOWE’S DEFENSE SINCE HUDSON’S ARRIVAL

Prior to the arrival of Head Coach Zack Hudson, Howe gave up 38.10 points per game on defense which was worst in school history. In Hudson’s first year, the Bulldogs improved by 139 points allowed, giving up 24.2 points per game. In 2015, in his third year of implementing his defense, the ‘Dogs gave up 14.42 points per game which was the least amount since 2000 and ranked 29 of the 72 Howe defenses. In 2016, Howe gave up 21.77 points per game in arguably the toughest district in any district in the state.

HOWE VS. GUNTER HISTORY

The is matchup #32 with Gunter. Howe leads the overall series with Gunter, 18-13-0 and have outscored the Tigers, 604-579.

The Bulldogs were 17-1 until 2000, but lost 11 straight to the Tigers. The streak ended in 2015 with a 21-19 win. Prior to 2015, Howe’s had been waiting since 10/17/1997 when Howe traveled to Gunter and won, 26-23 which is the last game Howe has won at Gunter.

Howe’s last win at Bulldog Stadium vs. Gunter happened in 2015, a 21-19 barn-burner. Prior to Howe’s home win in 2015, the last home win vs. Gunter was a 21-7 victory on 10/18/1996.

| 11/1/1935 | 31 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 6 |

| 10/30/1936 | 18 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 6 |

| 11/19/1937 | 7 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 6 |

| 11/4/1938 | 43 | at Gunter | 0 | |

| 11/17/1939 | 6 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 0 |

| 10/25/1940 | 54 | at Gunter | 7 | |

| 10/10/1941 | 33 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 6 |

| 10/12/1944 | 20 | at Gunter | 6 | |

| 10/12/1945 | 26 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 0 |

| 10/18/1946 | 20 | at Gunter | 0 | |

| 10/17/1947 | 34 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 0 |

| 10/14/1948 | 25 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 0 |

| 10/22/1958 | 0 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 42 |

| 10/15/1959 | 34 | at Gunter | 6 | |

| 9/8/1960 | 34 | at Gunter | 14 | |

| 10/27/1960 | 48 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 6 |

| 10/18/1996 | 21 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 7 |

| 10/17/1997 | 26 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 23 |

| 10/27/2000 | 14 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 15 |

| 10/26/2001 | 6 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 12 |

| 10/22/2004 | 6 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 34 |

| 10/21/2005 | 7 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 42 |

| 9/29/2006 | 8 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 35 |

| 9/28/2007 | 0 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 55 |

| 10/3/2008 | 0 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 49 |

| 10/2/2009 | 7 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 47 |

| 9/21/2012 | 27 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 42 |

| 9/20/2013 | 0 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 19 |

| 10/10/2014 | 14 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 33 |

| 10/9/2015 | 21 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | 19 |

| 8/26/2016 | 14 | at Gunter | Tiger Stadium, Gunter, TX | 42 |

| 9/1/2017 | Gunter | Bulldog Stadium, Howe, TX | ||

| 604 | 0 | 0 | 579 |

All-time coaching wins

Norman Dickey, 51 (1964-75)

Jim Fryar, 41 (1985-89)

Davey DuBose, 34 (1996-2000)

Buck Smith, 29 (1980-1984)

*Zack Hudson, 29 (2013 -)

All-time coaches .500 or better

Leslie Walden, .900, 18-2 (1938-39)

Wesley Cox, .900, 9-1 (1940)

John B. Lair, .889, 8-1 (1945)

Jack Osborn, .842, 16-3-1 (1946-47)

Cory Crane, .818, 9-2, (2010)

L.B. Morris, .765, 13-4-2 (1936-37)

Self Coached, .750, 3-1-1 (1942)

Jim Fryar, .719, 41-16-1 (1985-89)

Alfred Clayton, .692, 9-4-2 (1943-44)

H.A. McDonald, .667, 6-3 (1941)

Davey DuBose, .630, 34-20 (1996-2000)

*Zack Hudson, .604, 29-19 (2013-)

Curtis Christian, .600, 12-8 (1960-61)

Barnes Milam, .600, 6-4 (1935)

Buck Smith, .580, 29-21-1 (1980-84)

ON THIS DAY IN BULLDOGS HISTORY

9/1/2006, Howe lost at Blue Ridge, 36-13

Howe ISD releases bond information flyer

Rumor Central

Abby’s Restaurant in Downtown Howe will be closed for a week starting Aug. 26 through Sept. 4. The restaurant will reopen on Sept. 5 with regular business hours. The closure is due to the restaurant owner acclimating her youngest daughter to first-time college life in California.

“I need four days to get her settled in and three days to cry,” Abby’s owner Lillian Avila told the Enterprise.

In Small Town, Texas, rumors can sometimes do great damage to small businesses and Avila wants to let Howe and surrounding communities know why they will be closed so that wrong information does not spread.

Local small businesses are the backbone of America. Shopping local renews and strengthens your home town and helps neighbors pay for things such as college.

Monday’s eclipse brings reminder of the history of the spectacular event

by Ken Bridges

On Monday, August 21, viewers in the continental United States will be witness to a rare, spectacular event: the total eclipse of the Sun by the Moon. This will be the first total eclipse of the Sun seen in the United States since 1979. And Texas will be able to enjoy most of the event in spectacular fashion.

Though the Moon orbits the Earth every 28 days, the alignment of the Earth, the Moon, and the Sun to produce an eclipse only happens rarely. A wide arc of the US will fall into total darkness on August 21 as the eclipse crosses the nation, from Salem, Oregon, curving across to Casper, Wyoming, to Missouri through Kansas City and St. Louis, then to Nashville, Tennessee, and down to Charleston, South Carolina. The path of the totality, or area of total eclipse, will be about 70 miles wide and viewers in the zone of the totality will be under a total eclipse for roughly two minutes as the Moon’s shadow crosses the Earth at a speed of 2000 miles per hour.

Eclipses have been sighted for centuries. Among the earliest recorded eclipses occurred in ancient Mesopotamia in 1375 BC. Ancient Egyptians, who worshipped the Sun, were reportedly so disturbed by the bad omens associated with eclipses that they would never mention or write about them, fearing bad luck. Some scholars have pointed to eclipses in AD 29 and AD 33 as possibly being the eclipses observed during the crucifixion of Christ.

Historically, eclipses have been met with both fascination and dread. The Chinese believed that dragons were eating the Sun, causing an eclipse. An old Choctaw legend held that a black squirrel caused solar eclipses when it tried to eat the Sun and that the people needed to make noises to scare it off. Similarly, the Cherokees believed that a giant frog jumped onto the sun to cause the eclipse and that the people must beat drums and make loud noises to scare it away. For generations, Navajos believed that they should not eat during an eclipse or they would experience digestive problems. Navajo traditions also warned against looking at the Sun during an eclipse, or they would go blind. The ancient Mayans were able to carefully calculate when eclipses would occur.

Eclipses have also been an important tool for scientific discovery. Astronomers discovered a new comet during an eclipse in AD 418. The Sun’s corona was first noticed in an eclipse in 968. In the eighteenth century, solar prominences, eruptions on the Sun’s surface, were observed. These all helped give important information on how the Sun worked. The first eclipse photographed was in 1860. Eclipses in 1919 and 1929 helped confirm Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity by confirming that the light of stars traveling near the Sun was bent by the Sun’s intense gravity.

The maximum eclipse for August 21 for West Texas and the Panhandle will occur around 12:55 PM. For eastern Texas, this will occur at about 1:15. The beginnings of the eclipse will occur around 11:30 AM in West Texas and at 11:45 AM in East Texas. In Grayson County and northern Collin County, viewers will see 83% coverage, peaking at 1:09 PM. Viewers in Northeast Texas will get the best view, with 85% of the Sun eclipsed in Texarkana. The eclipse will end around 2:30 PM.

Viewers must remember that they should never look at the Sun directly. Even with most of the Sun obscured, the glare is too intense for the human eye to tolerate. Looking directly at the Sun is dangerous and could cause permanent eye damage. Not even regular sunglasses or binoculars are safe. Darkened Welder’s glass is the only safe glass dark enough to view an eclipse through. The classic pinhole projector will offer safe viewing: simply poke a small hole through one sheet of paper (poster board or cardboard can also work) and allow the fading sunlight to project onto another piece of paper.

NASA has unveiled a website for the eclipse, including tips on viewing the event safely at https://eclipse2017.nasa.

An even more exciting eclipse for Texans will occur on April 8, 2024, as a total eclipse will be observed crossing the heart of the state, with a totality of more then 100 miles wide. The totality in 2024 will cross Eagle Pass, San Antonio, Austin, Waco, Dallas, Fort Worth, and Texarkana.. Nature offers incredible wonders when we are willing to observe.

Dr. Bridges is a Texas native, writer, and history professor. He can be reached at drkenbridges@gmail.com.

Howe ISD officially calls for November bond for new school campus

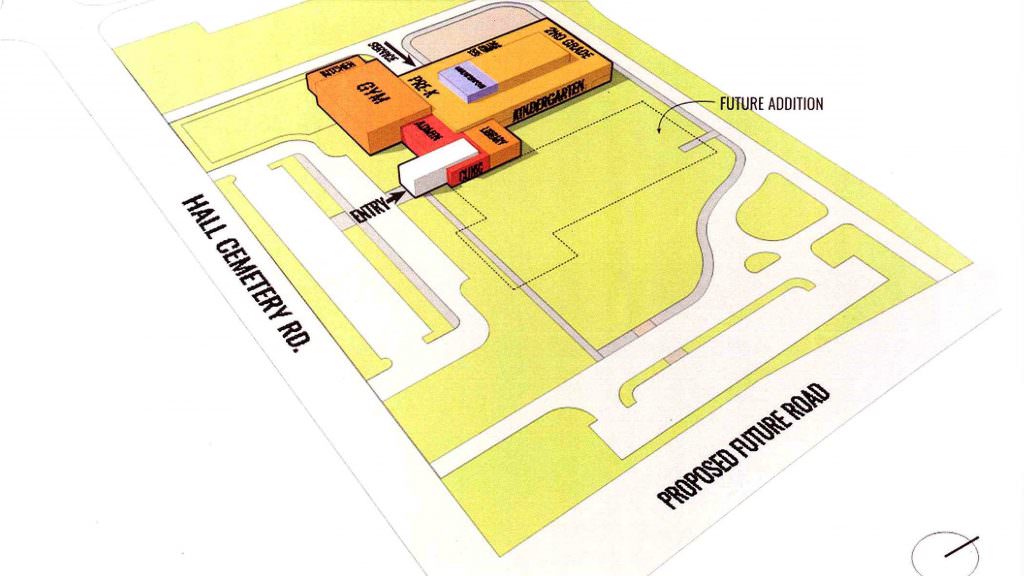

On Monday night, August 14, the Howe ISD Board of Trustees approved a motion to call for a bond election on November 7 of this year for a new Pre-K through second-grade campus to be located on a proposed location at Hall Cemetery Road near Western Hills. The bond amount will be $17 million. The campus will have a student area of 750 students with a classroom area of 400 students which is roughly the size of the current elementary school.

In previous meetings, the community facilities committee, after hearing all options from consultants, gave the recommendation to the board of razing the 1938 WPA former school structure located at the administration office. On that small four-acre lot, the only viable option was for a two-story intermediate school that would house grades third through fifth. However, recently a land developer has approached Howe ISD with a proposed land transaction from west of Western Hills to a now proposed 12-acre area just east of Western Hills on Hall Cemetery Road. The swap of allocated property was crucial due to utilities, such as water and sewer which are available on the new allocated property.

If Howe ISD voters approve the $17 million bond in November, work will proceed towards construction in the spring of 2018 and the new school would be scheduled to open in August of 2019. Should the bond fail, the elementary and middle school campuses will have to add multiple portable buildings on the site, presumably on Highway 75, in order to accommodate the overgrowth of the campus. A new full-scale elementary school was not an option due to the approximate $25 million cost being more than the current ISD’s bond capacity.

Texas Sales Tax Holiday This Weekend — Aug. 11-13

(AUSTIN) — Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar reminds shoppers the annual sales tax holiday is scheduled for this Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Aug. 11-13.

The law exempts most clothing, footwear, school supplies and backpacks priced for less than $100 from sales tax, saving shoppers about $8 on every $100 they spend during the weekend.

Lists of apparel and school supplies that may be purchased tax-free can be found on the Comptroller’s website at TexasTaxHoliday.org.

This year, shoppers are expected to save an estimated $87 million in state and local sales taxes during the sales tax holiday, which has been an annual event since 1999.

55.12 Howe Enterprise August 7, 2017

Howe fifth grader is number one shot putter in the nation

Braden Ulmer, an incoming fifth grader of Howe, just threw a record best shot put throw of 29.4 feet at nationals in Kentwood, MI. That throw was enough to land him the title of “Best in the U.S.” He is the son of Terry and April Ulmer of Howe.

Ulmer is a member of the Sherman Elite track organization.

Howe police and fire get Dallas TV recognition for helping save Plano Fire Captain

WFAA-TV

“”

NBC-5